| ________________

CM . . .

. Volume XXII Number 32. . . .April 22, 2016

excerpt:

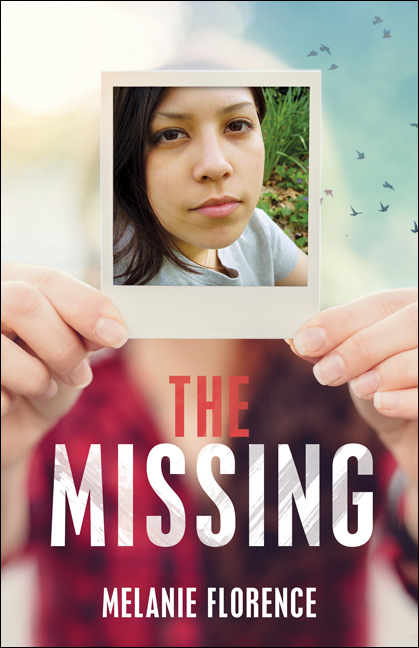

Carli Thomas, a “funny, quiet girl who cracked little side jokes . . . in Chemistry, who was one of the smartest girls . . . but who never spoke up in class, was missing. Maybe worse . . .” (p.17) Shuttled from one foster home to another since her mother’s incarceration for dealing meth, Carli has experienced a chaotic life. To escape the chaos, she’d sometimes take off to sit and read in Bonnycastle Park near Winnipeg’s Forks area, hang out at the Forks’ Riverwalk, or head for the rec centre nearby which served as a drop-in shelter and hang out for kids with lives like hers. Unlike Carli, or her close friend Mia Joseph, Feather Bedard’s family life is a model of stability. They may live in Winnipeg’s inner city where alcoholism and domestic violence are a commonplace, but Feather, her brother Kiowa, and her mom are close. Feather describes her mother as “the strongest woman I knew”, a single parent who “had worked hard to give us a good home while putting herself through school, and then . . . worked her way up the ranks” (p. 23) to be the head of marketing for a big hotel chain. As for Mia, her mom is rarely home because she works at two dead-end jobs; Mia’s father died of a drug overdose, and Joyce Joseph currently lives with and supports Leonard, “a nasty drunk who, instead of getting angry when he drank, got friendly. Too friendly. Inappropriately friendly.” (p. 28) How inappropriate? Well, Leonard’s grabbing and groping of Mia happens only when Joyce is at work, and recently Mia has installed a lock on her bedroom door. When Feather confronts Mia about the need to tell her mother about Leonard’s behavior, her tough-talking friend stonewalls, saying that she’ll head for the rec centre if things get really bad. Although Carli’s disappearance fuels the cruelest sort of rumor-mongering, within a couple of days the high school gossip mill turns its attention to Matt and Dre who have been outed for public displays of attention. Matt is a long-time friend of Feather’s, and she is disgusted at her fellow students’ trash talk about both Matt and Carli, but in discussing Matt’s plight with Mia, Feather learns that Carli has been forced to trade sex for dollars when desperate for cash. And when Feather’s boyfriend, Jake, meets her between classes, his first comment about Matt is concern that “he’s been checking me out in the change room” (p. 39) after gym class. Jake’s homophobia surprises Feather, and her surprise turns to shock when Jake states that he doesn’t care what Matt’s sexual preferences are “as long as he doesn’t get all faggoty around me.” (p. 39) A week after Carli’s disappearance, the police have done little to find her – to them, she’s just one more missing Aboriginal kid. One evening, during have a dinnertime discussion about the nationwide epidemic of missing and murdered Aboriginal women, Kiowa relates his experiences of racism when looking for a summer job, and Feather discloses that she and Mia are routinely victims of sexual harassment on the street or at the mall. Feather and her mom both express concerns about each other’s safety, and then Jake calls. Carli’s body has been retrieved from the river. When the news hits the high school, the student drama queens have a heyday. Later, Carli’s death will be judged a suicide. As Officer Dawson puts it, “Just another depressed Indian girl taking a swan dive into the river.” (p. 50) While there’s not much she can do about the histrionics and lurid speculation or the police inaction, Feather is outraged. Meanwhile, Mia finally has summoned the courage to tell her mom the truth about Leonard. Not only does Leonard claim that Mia has been throwing herself at him, Joyce offers her daughter an ultimatum: apologize to Leonard or leave home. Feather tells Mia to stay at her place, but Mia insists that she’s going to the rec centre. Like many teens, Mia goes nowhere without her phone, and when Feather receives neither mail, text, nor calls from her friend, she begins to get very worried. Desperate to find Mia, and after a frustrating visit with Joyce and Leonard, Feather and Jake go to the police station, but that proves equally fruitless. As they tell the story to Constable Perkins, it’s clear that, while Mia is a missing person to them, in the eyes of the police, her history tags her as “a habitual runaway.” (p. 98) A visit with the rec centre’s administrator doesn’t yield any leads, either, and when Feather is back home and begins a computer search for information about “missing and murdered Indigenous women”, her heart sinks. For a book that’s only 185 pages long, Melanie Florence has managed to pack a great many issues into The Missing: the numerous unsolved cases of missing and murdered Aboriginal women and the pain that it causes to those close to them, sexual abuse within families, a dysfunctional foster-care system, relationship violence, high school homophobia, and the impact of racial stereotyping. It’s hard to present all of this in an accessible manner for a young adult readership, but the book really succeeds. Feather is someone that anyone would want for a friend or a student: caring, loyal, and determined, she’s also full of fun and has a wry sense of humour. When Mia reminds a group of fellow female students that “We’re not all on drugs, bitch. But we do all know how to hunt.” (p. 11), Feather comments, “I don’t know how to hunt,” . . . Do you know how to hunt?” (p. 11) Melanie Florence certainly has an ear for authentic teen dialogue, and it breaks your heart when you start to realize that the friendship between Feather and Mia will probably end with tragic loss. The story is set in Winnipeg, but the high school attended by Mia and Feather could be any high school; certainly, there are always nice kids, but the mean girls, sexist jocks, and racist loudmouths who bottom-feed on the sad stories of Carli, Matt and Mia aren’t mere stereotypes. Feather, her mom, and Mia are all strong women, but, for the most part, men present badly in this novel: the police are, at best, dismissive, and more typically, rude, racist, and unwilling to pursue the disappearance of yet another young Aboriginal woman; Jake alternates being “the perfect boyfriend” and a homophobic jerk; and Leonard’s sole virtue is his ability to cook up a great meal. Michael, the director of the rec centre, seems nice, but seems ineffectual at dealing with the negligence of his co-worker, Larry. Only Kiowa, Matt, and Ben (Carli’s heart-broken boyfriend) seem consistently decent and supportive men. As a life-long Winnipegger, I found the references to familiar sites and landmarks added another dimension of realism to the novel. I did find it rather puzzling that, living at the school’s dorm, Kiowa would take a car to University of Winnipeg; the U of W is an urban campus and downtown parking is expensive. Where would he keep it? And, there were a few editing slip-ups. For example, after a candlelight vigil held at the rec centre in support of Carli and Mia, Feather receives a phone call from a stranger who identifies himself as Paul Abenaki and whose girlfriend died in mysterious circumstances, her body being found on the Riverwalk, under a bridge leading to downtown Winnipeg. In reporting the conversation, the caller is “Paul”, but when Feather hears his story, she replies “”Oh my God . . . Tom, I’m so, so sorry.” (p. 150) Similarly, when Jake and Feather are looking for evidence which will provide an alibi for Kiowa, they go to the gas station where Kiowa fueled his car on the night of Mia’s disappearance. he station attendant’s name tag identifies him as “Patrick”, and Feather initiates the conversation with “Excuse me? Hi. Patrick”? But, after the three discuss how often the gas station’s CCTV tapes are kept, Patrick morphs into “Paul”. However, these are minor faults in an otherwise powerful story. I think that the intended audience for the story is in the upper grades of high school, Grades 10-12, and, because it contains language and sexual content which are bound to offend someone, read the book completely before recommending it either as a choice for leisure reading or for use in an English/Language Arts or Aboriginal studies class. Since the book does explore so many racial and social issues, I believe that it would also make a good choice for a Sociology course. This isn’t “chick lit” by any means, but, because so much of the focus is on the friendship of Feather and Mia, I think that it will have greater appeal to young female readers. Despite its title, the article, “Welcome to Winnipeg”, published in the February 2, 2015 issue of Maclean’s, made it clear that Winnipeg is less-than-welcoming to its large Aboriginal population. In 2015, the body of 15-year-old Tina Fontaine was pulled from the Red River, and in January of 2016, 16-year-old Rinelle Harper was sexually assaulted and left for dead in the Assiniboine River. Rinelle lived to tell her story in Winnipeg, asking publicly for an inquiry into the situation of missing and murdered Aboriginal women. Like Rinelle, and like Feather, readers might wonder, “Why aren’t newspapers reporting more of these disappearances? How can there be so many unsolved murders in one group? Why doesn’t anyone care? Why isn’t someone doing something? Why are they letting more girls go missing?” (p.111) Buy copies of The Missing for your high school library novel collection, encourage English teachers to read it and consider it as a supplemental novel choice for high school English classes, and certainly, for any Aboriginal studies class. Just make sure that you have a good rationale written up to support a book which deals with the gritty realities of teenage profanity, gay students, racial stereotyping, and last but not least, adolescent sexuality. Highly Recommended. Joanne Peters, a retired teacher-librarian, lives in Winnipeg, MB.

To comment

on this title or this review, send mail to cm@umanitoba.ca.

Copyright © the Manitoba Library Association. Reproduction for personal

use is permitted only if this copyright notice is maintained. Any

other reproduction is prohibited without permission.

Next Review |

Table of Contents for This Issue

- April 22, 2016. |